Written 28 August 2025 · Last edited 20 November 2025 ~ 11 min read

Multi-layer Perceptrons and Backpropagation

Benjamin Clark

Part 3 of 3 in Foundations of AI

Multi-Layer Perceptrons and Backpropagation

Introduction

As covered in the previous articles about perceptrons and activation functions, modern activation functions allow non-linear classification but perceptrons are designed for binary classification.

So to to take advantage of non-linear activation functions it follows that we need a bit more than a simple perceptron.

So, what if… we just stack them up? Three perceptrons in a trenchcoat a neural network doth make (sort of).

The Goal

By the end of this article, you will understand:

- Why stacking perceptrons into layers creates more expressive models.

- The structure of an MLP (input, hidden, and output layers).

- A brief introduction to backpropagation

A (brief) recap on the Perceptrons limitations and XOR

As perviously mentioned perceptrons simply compute a weighted sum and apply an activation:

y=f(i=1∑nwixi+b)Where:

- y = perceptron output

- f = activation function

- wi = weight for input xi

- xi = input feature

- b = bias term

- n = number of input features

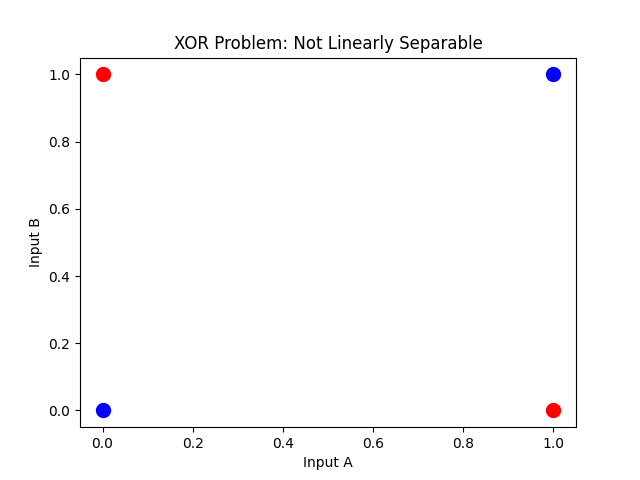

However, some problems are not linearly separable. For example, XOR is a classic example:

| Input A | Input B | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

There is no single straight line that separates the 1s from the 0s. So the Perceptron falls flat on its face.

The XOR limitation was highlighted in Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert’s Perceptrons (1969), which proved that single-layer perceptrons cannot represent linearly inseparable functions such as XOR. This helped trigger a decline in neural-network research until multi-layer training revived the field in the 1980s.

Perceptrons: An Introduction to Computational Geometry (MIT Press, 1969)

Solving XOR

Solving the XOR problem requires, at least, two layers:

- First layer: constructs intermediate features.

- Second layer: combines them to form the final decision.

Lets move away from the (slightly ludicrous) Eques example I used when explaining Activation Functions, and onto a much more sensible “will I eat this cake” example.

The first layer of the neural network detects features I’m interested in:

- How expensive is the cake to buy?

- Is it chocolate?

- Does it look yummy?

- Am I full?

These then feed into a second layer, which applies weightings and bias to each discovered feature to produce a final decision.

In other words, we deconstruct the input into features we care about, and make decisions based on these features rather than on the direct input itself.

Mathematically, instead of a single transformation

y=f(w⋅x+b)We compose layers:

y=f(2)(W(2)f(1)(W(1)x+b(1))+b(2))Where:

- f(1),f(2) = activation functions for the first and second layers

- W(1),W(2) = weight matrices

- b(1),b(2) = bias vectors

- x = input vector

This composition of functions gives MLPs their expressive power. Each layer builds on representations created by the previous one, enabling the network to discover features inherent in the data and make decisions based on their combination.

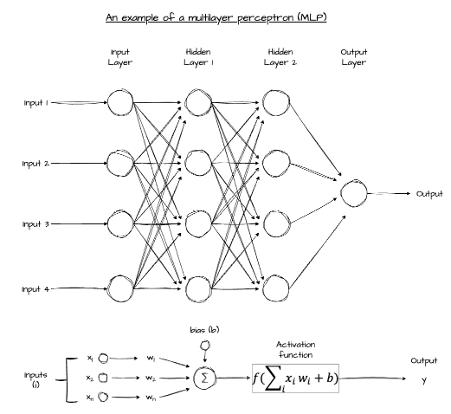

Structure of a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

An MLP typically contains three types of layers:

- Input layers - receive the raw input.

- Hidden layers - contain neurons which compute a weighted sum, add bias, and pass the result through a non-linear activation function to extract features.

- Output layer - one final layer to produce the result of the network

These hidden layers act as a black-box. Their weights and bias are discovered automatically, rather than configured, and tweaking them to produce optimal results is more than art than it is a science. This remains a real problem for explainability; if a neural network is deciding on your mortgage renewal, or a court case, then - ethically - you probably want to concretely know why it made the decisions it did rather than simply guess. With deep neural networks figuring this out is a topic of ongoing research, whilst some organisations opt to utilise expert-models instead to ensure full tracability in decision-making.

Regardless, focusing on MLPs per layer the mapping becomes:

h(l)=f(l)(W(l)h(l−1)+b(l))Where:

- h(l) = output vector from layer l

- h(l−1) = input vector to layer l (output of layer l−1)

- W(l) = weight matrix for layer l

- b(l) = bias vector for layer l

- f(l) = activation function at layer l

A Simple Example (Digit Classification)

A common use-case when trying to explain this sort of thing is classification of handwritten digits between 0-9 utilising the (MNIST) dataset, and I don’t see any real reason to deviate from that.

Supposing each image is 28x28 pixels, a minimal MLP might contain:

- An input layer with an input size of 784 (our 28x28 pixel image flattened into a vector)

- A hidden layer with 16 neurons, utilising non-linear activation, to discover things like “are these group of pixels rounded or not”

- An output layer with 10 neurons - one digital per class - which is then normalised and passed through softmax.

Softmax maps a length-k logit vector to a length-k vector of non-negative values that sum to 1.

In other words, all of the non-activations mentioned will probably output values that sum to more than one. If we feed them to softmax, we instead get a single-vector representing a probabilistic distribution across k class.

y^i=softmax(z)i=∑j=1kezjeziWhere:

- z∈Rk = logits (the raw values from our activations)

- y^∈(0,1)k = normalised outputs (the probabilistic distribution)

- ∑i=1ky^i=1 = normalisation (on the probability simplex)

For example:

- Logits: [2.0,1.0,0.1]

- Softmax: y^≈[0.66,0.24,0.10]

Structure isn’t all an MLP requires though. I mentioned earlier that the weights and bias for a network are learned, so I should probably explain that next.

With the layers defined, the next question is how to make the parameters fit the data. We start by defining a loss and a rule for updating the weights.

How MLPs learn

Figuring out how to adjust the weights and bias in a network intuitively requires two things:

- Figuring out how wrong the model is in its predictions

- Nudging each weight/bias appropriately by how much we think it contributes to the “wrongness” of the network

Formally, how “wrong” the network is may be defined by a “loss” function and weight/bias correction may be defined as a learning “rule”. “Backpropagation”, which applies these concepts to an MLP, will be examined in the next major section of this article.

Loss Functions

A loss function allows us to figure out, during training, how “wrong” a prediction is. What type of loss function we utilise really depends on what kind of prediction we wish the model to make. Mean-squared error (MSE) is usually used when we wish for the model to predict a continuous value, whereas Cross-Entropy is usually used when we wish for the model to classify input into one or more classes.

For example:

- MSE may be useful if we wish a model to predict revenue in the next quarter

- Cross-Entropy may be useful if we wish a model to perform sentiment analysis

Mean-squared error (MSE)

L=n1i=1∑n(yi−y^i)2Where:

- n = number of samples

- yi = true value

- y^i = predicted value

Cross-Entropy

L=−log(y^c)Where:

- c = index of the correct class

- y^c = predicted probability for class c

Optimisation as a learning rule

Once we’ve calculated an appropriate “loss”, we need some way of figuring out how this should translate towards nudging weights and bias in an appropriate direction to achieve our desired result.

In other words, we need a way to optimise our loss.

Gradient Descent

During learning, if x is the values given, y are the true values we wish to predict, and y^ are the predictions we are trying to make, then it follows that xi, yi, and y^i are the values for the _i_th example in the dataset.

Thus, utilising a straight-line the prediction of values is

y^i=mxi+c

Where:

- m is the slope of the line

- c is where the line meets the y axis

Thus, the loss for each element is the different between the predicted, and actual, value squared. Loss for the entire dataset is average loss for each element which becomes:

L=n1i=0∑n(y^i−yi)2=n1i=0∑n(mxi+c−yi)2To learn, we can find the slope of the loss for the values of m and c. This allows us to understand how the loss value will change for small changes in m and c. Mathematically, we are interested in discovering the partial derivative.

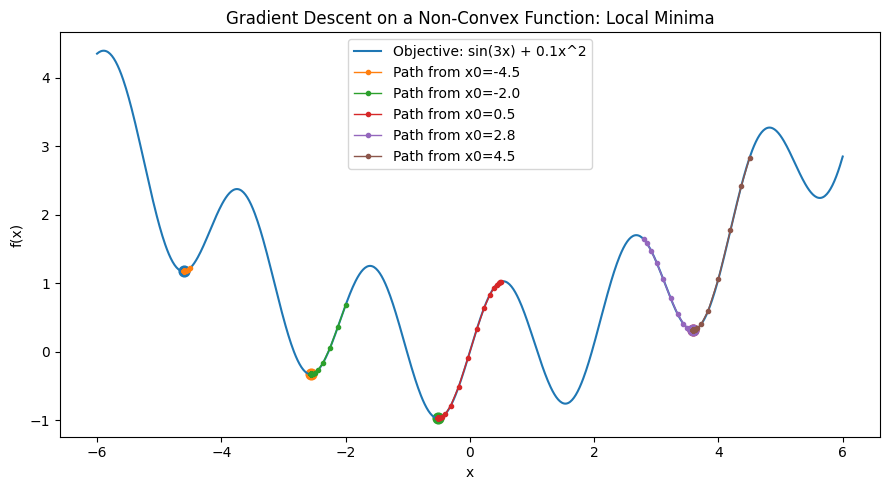

If, like me, you’re a visual learner than the graph below may help:

By calculating the gradient, we can determine whether to adjust our parameters up or down to move toward a local minimum. Finding the global minimum is much harder and often computationally impractical, since there’s no simple way to know whether the minimum we’ve reached is the absolute lowest point or just a local one. In practice, gradient descent aims for a “good enough” solution — one where the loss is acceptably low rather than perfectly minimal. Various techniques (such as using momentum, adaptive learning rates, or random restarts) help reduce the chance of getting stuck in poor local minima and improve overall convergence.

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

While standard (or “batch”) gradient descent provides a clear mathematical foundation, it quickly becomes inefficient as datasets grow large. Computing the gradient over the entire dataset at every update is computationally expensive and slow to converge.

To address this, machine learning practitioners often use Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) and its variants. Instead of computing the loss and gradient over the whole dataset, SGD updates the model using a single training example (or a small random subset called a mini-batch) at a time. This makes optimization faster, noisier, and often more effective in practice.

Backpropagation

Loss and gradient descent, combined, give an indicator of what direction to nudge weights and bias towards in order to find a local minimum. However, in a large neural network each individual weight influences the final output only indirectly, through many layers of intermediate computations.

Backpropagation provides a practical way to work out how each weight and bias contributed to the total loss. It relies on a basic idea from calculus: when one quantity affects another through several steps, we can work out the total effect by combining the small effects at each step (a.k.a the chain rule). BBC Bitesize has a clear introduction to this if you want some more detail.

Backpropagation works in three stages:

- Forward pass: the network computes predictions and stores all intermediate values (weighted sums, activations, layer outputs).

- Backward pass: starting at the output layer, we work backwards to calculate how a small change in each weight or bias would change the final loss.

- Gradient collection: this gives us the full set of gradients needed for gradient descent in a single, efficient sweep.

Without this process, we would have to recalculate every dependency for every parameter — something that becomes computationally infeasible even for modestly sized networks. With backpropagation, we can train deep models using any differentiable activation function and any gradient-based optimiser.

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve moved from single-layer percpetrons to multi-layer perceptrons, and examined some basic techniques for how they are trained.

Hopefully, you’ve learned:

- Why stacking perceptrons into layers creates more expressive models.

- The structure of an MLP (input, hidden, and output layers).

- A brief introduction to backpropagation

I’m going to take a break from writing blog articles for a while, but when I’m back I want to expand upon the topics I covered in my recent talk about Quantisation for the DevOps Society in Manchester. So keep your eyes peeled for that, at some nebulous point in the future.

Part 3 of 3 in Foundations of AI